Production is moving at such a pace and has become so routine that Lockheed’s vice-president for LCS, Joe North, sometimes forgets which ship comes next.

“We’re up here this week [for] the launch of LCS-11, which is the future USS Sioux City — I’m sorry, LCS-9, which is the USS Little Rock,” North said, chagrined, in a conference call from Marinette. “Later this year, we will be launching LCS-11, which is Sioux City.”

Losing track is understandable. “We currently have seven ships in production up here,” North told reporters. LCS-9 will

launch this Saturday and LCS-11 later this year. Work is well underway on LCS-13 and -15, while it has just started on LCS-17 is under production. LCS-19 and -21 are under contract, and Lockheed expects a contract for LCS-23 soon. (Even-numbered LCS are built by Austal in Alabama, which uses

a completely different design).

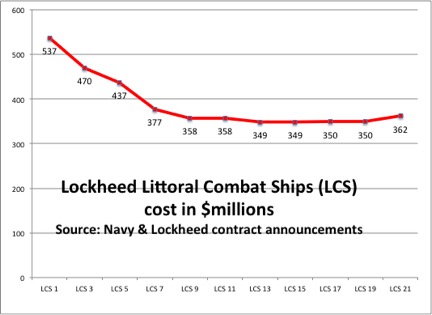

The cost is currently about $358 million for the Freedom version and headed down to a low of $348.5 million. (Note these figures are for the ship itself and don’t include military equipment, such as weapons, that the government purchases separately, which can add over $100 million). The price has dropped steeply since the mismanaged early days of the program, when the Navy changed the design of LCS-1 and -2 midway through construction. Now the price is starting to level out. Costs will eventually climb back up slightly: After years of making LCS manufacture more efficient, the shipyard is reaching diminishing returns, while inflation in labor and materials is beginning to catch up.

So what’s unique about LCS-9? The future

Little Rock is the first Lockheed LCS to be built entirely in Marinette’s revamped facilities. When Marinette was bought in 2008 by Fincantieri — on whose civilian designs the Lockheed LCS is based — the Italian company committed to a

$73.5 million investment in the shipyard, parts of which dated to World War II. The more streamlined manufactured process reduces the distance ship components travel through the yard by eight miles, North said.

LCS-5 and LCS-7 were built as the yard was renovated around them, which some work done in the old facilities and some in the new. LCS-9 was built entirely in the new.

“The one thing we will not to do is…break production,” said North, “because we’ve already bid these ships and we already have contracts in place for them.” That means keeping the design the same — and resisting any urges to “improve” it that might increase cost or impose delay.

That said, the Navy is looking at an

upgunned, upgraded, and more expensive variant of the LCS, designated a

frigate. The current plan is for 32 of the existing LCS designs and 20 LCS frigates, but there’s considerable interest in cherry-picking some of the frigate’s improvements and adding them to the original-model LCS.

North made clear, however, that such upgrades would not be allowed to interfere with ongoing production: They “would probably be [done] in a backfit mode once we’re done and delivered here,” he said.

Lockheed is already looking at how to modify its LCS into the frigate design — but the details of what weapons and other equipment it has to carry are still being decided by the Navy. “We’re working…on cost and weight reductions to account for the fact that you’re going to get rid of large open module areas and fill them in” with new systems, North said. “They’re supposed to have final definition later this year [and] tell us what

their final selection of systems is.”

CAPITOL HILL: The war over the Navy’s Littoral Combat Ship is

far from over. This morning, Senate Armed Services Committee chairman

John McCain warned Navy leaders that their drive towards

an upgraded LCS frigate may be repeating the mistakes that resulted in the original, much-criticized LCS design.

“Without a clear capabilities-based assessment, it is not clear what operational requirements

the upgraded LCS is designed to meet,” McCain said. “The Navy must demonstrate what problem the upgraded LCS is trying to solve. We must not make this mistake again.”

The biggest controversy over the Littoral Combat Ship has been

its inability to survive in combat. At this morning’s hearing,

Navy Secretary Ray Mabus acknowledged a small ship would never be as tough as a full-size destroyer but that “survivability — for a small surface combatant, particularly with the upgrades — meets our fleet requirements.”

That sounds okay, but it begs the crucial question: Are the requirements right? Meeting the standard doesn’t help if the standard is set too low. Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi reactor was designed with the requirement to survive anything short of a once-in-a-century storm, for example, but it turned out that 100-year-storm occurred a lot earlier than anticipated.

For another example, both the current and upgraded LCS designs have radically unorthodox hulls and disproportionately massive powerplants — with a complex combination of both diesel and turbine engines — because the Navy wants the ships to go faster than 40 knots. That’s staggeringly fast for a warship, about 30 percent faster than an Aegis destroyer. But no one in the Navy seems to have ever figured out

quite what to dowith all that expensive speed in a real-world tactical situation. It’s a solution searching for a problem.

Skeptics argue that launching helicopters, drones, and missiles provides far faster response at far less cost than trying to accelerate the whole ship. A requirement that sounded intuitively awesome to the admirals might have proven excessive if subjected to rigorous analysis, but that analysis wasn’t done.

The Navy did conduct a great deal of analysis before settling on the upgraded LCS designs — but much of that analysis was based on naval officers’ intuition and experience. A

Small Surface Combatant Task Force conducted extensive focus groups with experienced officers across the fleet, asking them to rate the value of different capabilities and make tradeoffs among them to determine the highest priorities. The SSCTF then used computer modeling to work through thousands of alternative designs, from all-new warships to foreign designs to modifications of the existing LCS, ultimately choosing a modified LCS

to absolutely no one’s surprise.

That was work worth doing, but it can’t replace the traditional process of formal analysis, Congressional Research Service analyst Ron O’Rourke argues in a

recent study. O’Rourke takes issue not with the Small Surface Combatant Task Force itself, but with then-Secretary Chuck Hagel’s

February 2014 memorandum that rebooted LCS in the first place.

“[There are] two formal, rigorous analyses that do not appear to have been conducted prior to the announcement of the program’s restructuring,” O’Rourke writes. Before you commit taxpayer dollars to a weapons program, you traditionally take three steps, he writes: “[1] identify capability gaps and mission needs; [2] compare potential general approaches for filling those capability gaps or mission needs…and [3] refine the approach selected as the best or most promising.” In short, you figure out what problem you’re trying to solve, then how to solve it, then how best to implement that solution. The upgraded LCS skipped the first two steps.

Specifically, the Small Surface Ship Combatant Task Force did Step No. 3. The SSCTF was created to examine existing, all-new, and modified designs for “

a more lethal and survivable small surface combatant, with capabilities generally consistent with those of a frigate.” After extensive analysis, the task force came up with the ship that met those criteria best. But it was Hagel’s memo that set those criteria. It did so with no evident analysis of what specific problem the frigate was supposed to solve. Nor was there analysis of whether a frigate was the best solution, as opposed to some other kind of ship or something else altogether — for example a larger ship, an aircraft, or new tactics.

“Having refined the design concept for [the upgraded LCS], the Navy will now define and seek approval for the operational requirements for the ship,” O’Rourke writes. “Skeptics might argue that definition and approval of operational requirements should come first, and conceptual design should follow, not the other way around.”

For an expert like O’Rourke to pose the question is itself significant: He’s

one of the most respected naval analysts around, and his job at CRS is specifically about advising Congress. For a bulldog like

McCain to promise oversight on the issue raises it to a higher level — one the Pentagon needs to deal with.

By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.on January 16, 2015 at 6:45 PM

CRYSTAL CITY: What’s in a frigate? That which we call a Littoral Combat Ship by any other name would smell as sweet — or stink as bad, according to LCS’s many critics. While LCS is being redesigned and renamed, there’s a lot of hard work and hard choices required to make the improvements real.

Navy Secretary Ray Mabus

“If you list the attributes of a frigate and then list the attributes of [an improved LCS], we’re actually more capable than a normal frigate is,” Mabus told reporters after his remarks to the

Surface Navy Associationconference. “They don’t look like traditional Navy ships sometimes, and I think that’s one of the issues that traditionalists have, but if you look at missions, if you look at what a frigate is supposed to be able to do, that’s what this ship does.”

The

basic plan set forth a year ago is to buy 32 Littoral Combat Ships of the current design, the last of them in the fiscal 2018 budget. Then the Navy will buy 20 of the upgunned version — what’s now the frigate — starting in fiscal 2019. The exact package of upgrades that will actually make the frigate a frigate won’t be finalized until ’19, but it will include more weapons, armor, and sensors.

The Navy wants to add at least some of these improvements to at least some the Littoral Combat Ships being built before 2019. “We’re going to try to fold in these new capabilities earlier than [LCS] 32,” Mabus said.

How many of them? “All of them,” Mabus hopes. “If we fold in some, we’re going to fold in all [the improvements]. It’ll add about $75 million a ship but, as we said, that’s still under the congressional cost cap. We’re not going to piecemeal it, we’re going to do the entire upgrade.”

The Secretary’s subordinates sounded somewhat less sanguine. “We’re going to want to do that [upgrade] across the board as best as possible,” said

Sean Stackley, assistant secretary for acquisition. But “this isn’t exactly a binary thing,” Stackley told reporters: It’s not an either/or where you either have to add the entire upgrade package envisioned for the frigate or do nothing.

Sean Stackley, Assistant Secretary of the Navy

“[Upgrades] to improve the survivability, we want to do those on all the ships,” Stackley said: extra armor around weapons magazines, for example,

shock hardeningaround vital equipment, or degaussing the hull to reduce its magnetic field. But the details of more complicated upgrades — such as missiles and electronics — will take a few years to figure out. In the meantime, he said, you might have to build ships with places for the systems-to-be-determined to plug in later.

Some of the Littoral Combat Ships already in the water may never get all the upgrades. Internal armor, for example, is such an integral part of a ship’s construction that it might be impractical or impossible to retrofit. “For ships that are already delivered, it may be such a large charge that we may only be able to do partial [upgrades],” said the Navy’s Program Executive Officer (PEO) for LCS,

Rear Adm. Brian Antonio.

There’s also the constraint of time, Antonio told reporters. “LCS-1 was commissioned in ’08, and with a 25-year service life, that takes her to 2023,” when she retires — which would be just four years after the upgrade design is finalized in 2019. Littoral Combat Ships come in for major maintenance every 32 to 36 months. So with the earlier ships, said Antonio, “there’s a mathematical possibility that we wouldn’t be able to get everything in.” (It’s also inefficient to invest in upgrading a ship about to retire).

Rear Adm. Brian Antonio

“We’ll catch as many as we’re funded [for] and can do,” the admiral said.

For every upgrade to the ship, there’s a delicate balance between how much combat capability it would add and how much time, cost, and complexity it would require. It’s worth remembering that the epic overruns and delays on the first two Littoral Combat Ships were caused primarily by a decision halfway through construction to change basic features of the design. Since then, the program has made only modest improvements from ship to ship, and it’s made remarkable progress controlling both cost and schedule.

“What I like is stability in the shipbuilding plan,” said Antonio. “Worst thing in the world would be, ‘hey, we’ve got this great new thing, we’ve got to go [add] it,’ and ship deliveries get delayed by six months, a year, two years, and all of a sudden everything’s out of whack.”

“It’s already going to be a sporty timeline,” Antonio said. What the Navy has to work from is the current LCS design — actually two designs, the

Lockheed-built Freedom class and the

General Dynamics Independence — and a detailed concept for the upgraded frigate version, developed over six months by the

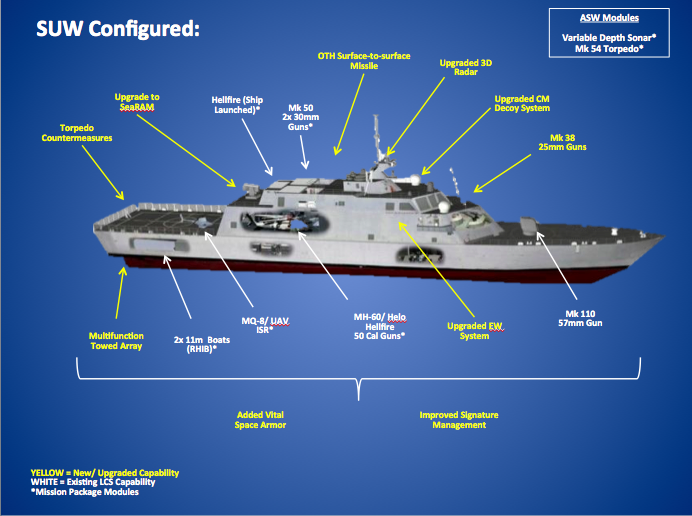

Small Surface Combatant Task Force. That concept calls for such improvements as new electronic warfare gear and a new “over the horizon” anti-ship missile with a 100-150 nautical mile range. It doesn’t specify such things as whether the minimum acceptable is 100 or 150 or something in between, what specific targets the weapon must be able to hit, what kind of seeker the warhead should have, let alone which missile to buy.

“The task force identified capability,” said Antonio. “We’ve got to identify the systems; then we have to identify how those systems integrate or interface with the current systems; and then there’s a whole development and testing [process] that has to happen.”

The upgraded version of the LCS-2 Independence.

How far along are we? Antonio has hired three former Small Surface Combatant Task Force staff to form a “concept development team” with full access to all the task force’s analysis: “That kind of gives me a jump start,” he said. He’ll soon be able to show both shipbuilders a “sanitized” version of the task force materials as well.

The Navy needs to take all the task force’s concepts for capabilities and translate them into specific, formal requirements, Stackley explained. Those requirements then need approval by a Resources and Requirements Review Board (R3B). Then, for each requirement, the Navy needs to decide if it can meet it with equipment already in service — which may require buying more items off existing contracts — or if it must hold a competition for something new. A Request for Proposals will go out to industry in 2018, with award and procurement in 2019.

Then it’s up to the winners from

industry to deliver the goods and to the government to integrate everything into a working warship. (The Navy is acting as its own “lead systems integrator” here rather than contracting that function out). Only then will the world be able to judge whether the final product is worthy of the name of “frigate,” an honorable heritage going back to the

USS Constitution.

By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.on December 11, 2014 at 9:35 PM

PENTAGON: The controversial Littoral Combat Ship dodged a big torpedo today, whenoutgoing Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel approved the Navy’s plan for a larger, better armed and better protected version of the ship. Critics had called for a radical redesign or an entirely new ship. The “modified LCS” simply adds new weapons, electronics, and armor to the two existing LCS variants for an additional $60-$75 million per ship.

“After rigorous review and analysis, today I accepted the Navy’s recommendation to build a new small surface combatant (SSC) ship based on upgraded variants of the LCS,” Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel said in a statement early this evening. “The new SSC will offer improvements in ship lethality and survivability, delivering enhanced naval combat performance at an affordable price.”

Arguably the biggest change: the new version will not be able to serve as a

minesweeper, focusing instead on fighting enemy surface vessels and submarines.

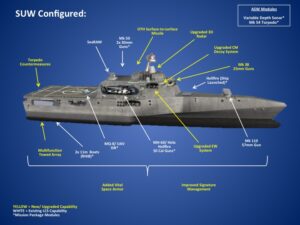

The upgraded version of the LCS-1 Freedom class

The Navy remains committed to buying both the speedboat-like

Freedom hull, built by

Lockheed Martin and

Marinette Marine in Wisconsin, and the space-age-catamaran

Independence, built by

General Dynamics and Austal in Alabama. Between them, the two teams will build 52 Littoral Combat Ships, as was the plan

before Sec. Hagel ordered a review of LCS in February. Today’s announcement simply means 32 of those will be the original LCS design and 20 will be the upgraded version. (At least some of the original 32 will eventually receive at least some of the upgrades, but the current design can’t accommodate all the changes).

The split between the teams and terms of competition remains to be determined: The Navy will submit

an acquisition strategy to the secretary by May and work out detailed cost estimates as part of the budget process for 2017. While the shipbuilders themselves will remain the same, there may be multiple opportunities to compete on specific components of the upgrade package, such as new missiles and sensors.

The upgraded version of the LCS-2 Independence.

So what’s the difference between the “modified LCS” and the current design (bizarrely designated “Flight Zero Plus”)? The new version gets a lot more combat power for not much more cost, insisted the Chief of Naval Operations,

Adm. JonathanGreenert, and the Navy’s top procurement official, Assistant Secretary

Sean Stackley, at a hastily convened roundtable with reporters this evening.

“Are you going to need an

Aegis ship to protect this ship? The answer is no,” said Stackley. One major criticism of the original LCS was that it lacked the anti-aircraft and anti-missile defenses to survive on its own against any serious threat, requiring escort by expensive cruisers and destroyers equipped with the Aegis defense system. While threat environments vary, Stackley said, “we have given this multi-mission [LCS] the degree of self-defense that it needs so it does not have to be operating underneath the umbrella of an Aegis ship.”

Unlike an Aegis ship, however, the new LCS design does

not have the Navy’s standard multi-purpose missile-launcher, the Vertical Launch System. Used on larger craft from cruisers to attack submarines, VLS can fire different kinds of rounds to shoot down incoming aircraft and missiles, strike land targets, or — once the Navy finishes developing a new long-range anti-ship missile — sink enemy warships. Outsiders, including

one of Greenert’s former aides, argued an LCS with VLS would be much more able to attack a wide range of targets and defend itself or even other ships against a wide range of threats.

Adm. Jonathan Greenert briefs reporters on the new LCS

“They did evaluate a Vertical Launch System,” Adm. Greenert said. But it was “kind of heavy, kind of big, a major change [adding] cost, time. It was all part of the evaluation, Sydney, so it was considered.” But ultimately the

Small Surface Combatant Task Force charged to review alternatives to the current LCS found adding a Vertical Launch System cost too much in terms of money, production delays, and weight for what it added, Greenert said.

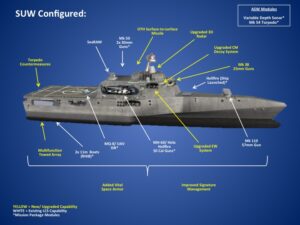

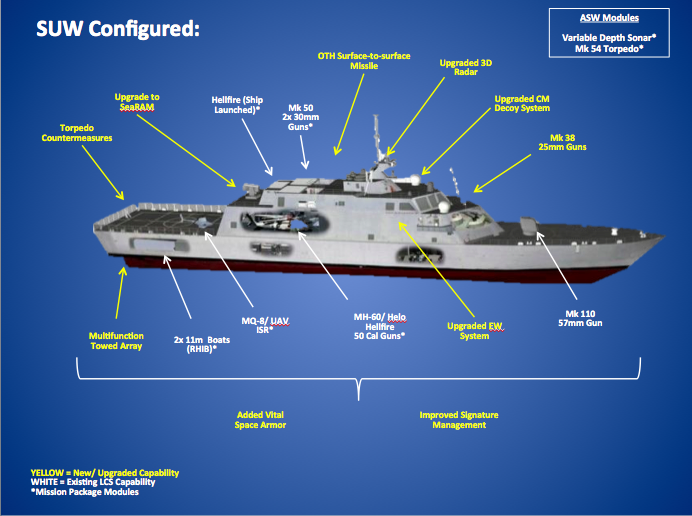

What the new LCS

will have, and the current one does not, is an over-the-horizon anti-ship missile: The Navy will probably hold a competition for the exact system, but Stackley said it would be at least comparable to the

Harpoon Block II, which has about a 70-mile range.

For self defense, the new LCS will have an upgraded version of the current model’s

SeaRAMmissile launcher. It will also add new

25 millimeter heavy machineguns. (The Navy decided against adding a 5-inch cannon, though, to traditionalists’ dismay). It have new decoy launchers and anti-torpedo defenses. An advanced

degaussing system will make the hull’s magnetic field less detectable by naval mines.

To detect threats, the new LCS will have an upgraded radar and a “multifunction towed array” to detect torpedoes and submarines. When configured for all-out sub hunts, it will replace some of its anti-ship weapons with a variable-depth sonar — making it, said Stackley, “the most effective ASW [anti-submarine warfare] platform in the Navy.”

A Vertical Launch System (VLS) firing.

From Adm. Greenert’s perspective, though, the most exciting new addition “would be the upgraded EW [

electronic warfare] system,” he said. While the new LCS won’t get the full

Surface Electronic Warfare Improvement Program (SEWIP) Block II being developed for larger warships, it will get what Greenert called “SEWIP-light.” That allows for a “soft-kill” of incoming missiles, not by shooting them down but by scrambling their electronics.

Finally, if the enemy does manage to land a blow, the new LCS will be much better able to survive and recover, Stackley said. Crucial compartments on the ship will have additional armor and key systems will be hardened against shock. While the Navy doesn’t use its traditional Level 1/2/3 system of survivability ratings anymore, Stackley said the new LCS’s robustness “matches what we would have for a frigate” — a significantly larger class of vessel that Hagel himself ordered the Navy to consider as a replacement for LCS.

So how can the Navy cram all this new stuff into the existing hull designs? The current LCS is built as a “modular” design that can configured as a minesweeper, sub-hunter, or anti-ship combatant — but not all three at once. The new LCS, by contrast, will need some plug-and-play systems for specific missions, but it will always carry both its over-the-horizon missile launcher — an anti-ship weapon — and its towed array — anti-submarine — in addition to the new defenses.

Sean Stackley, Assistant Secretary of the Navy

That’s possible because the task force scoured the LCS design for places to cut weight. “We’ve looked at every item on the ship,” Stackley said. Every pound nipped and tucked from non-essential systems was more for weapons, sensors, and armor. That process will continue as designs get more detailed. It’s likely the new LCS will end up somewhat heavier than the current design, Stackley said, but that will only slow the ship by a few knots. That’s not a major sacrifice given that the Navy designed the LCS for a blisteringly fast 40-plus knots and then

struggled to figure out what, tactically, all that speed was for.

The one real sacrifice in the new LCS design is the

ability to clear mines. That mission will be left to the 32 original-model Littoral Combat Ships — which, Greenert insisted, was enough to handle “the most stressing” possible scenarios. What the theater commanders around the world wanted most, Stackley said, was not minesweeping but the ability to combat both surface craft and submarines. That is the mission against which the new LCS will be measured.

No comments:

Post a Comment